FGF E-Package

The Ornery Observer

October 8, 2012

The Late, Great Joe Sobran

by Paul Gottfried

fitzgerald griffin foundation

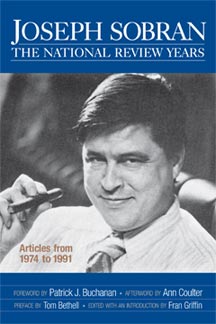

Joseph Sobran: The National Review Years. (Vienna, Virginia: FGF Books, 2012.)

ELIZABETHTOWN, PA —Recently I received the galleys for the anthologized essays and book reviews by the late, great Joe Sobran (1946-2010). The anthology pieces come out of the period when Joe was working at National Review, a relation that started in 1972 and allegedly ended because of irresolvable political differences in 1993. The essays are made even more inviting by Pat Buchanan’s foreword, Ann Coulter’s afterword, Tom Bethell’s preface, and publisher Fran Griffin’s eloquent introduction. The book features a cover portrait of Joe while still in his prime, nattily dressed and sporting a Menckenesque cigar.

One value of this anthology is that it reveals a brilliant social commentator outside the confrontational context in which he spent most of his life’s last two decades. Because of his dogfight with the American Zionist lobby that resulted in a series of Sobran’s critical, sarcastic comments about Jewish influence on the media, Joe found himself professionally and, except for a few steadfast friends, socially isolated. He was also unfairly accused of Holocaust denial, which he might have avoided had he not spoken on a totally unrelated topic at a conference sponsored by the Holocaust-denying Journal of Historical Review in 2002.

But the attacks would have kept coming no matter what. Joe took on powerful enemies whom he couldn’t match in firepower. The last few years of his relatively short life were also marred by health problems, and I recall seeing Joe during this period looking frailer each time I encountered him. I’ve been told that only toward the end did he lose his wit and proverbial way with words.

In this anthology, however, one meets a political and social writer with a sense of language that I found unmatched among my contemporaries. (And I’m including Buckley, who for all his personal flaws could turn a phrase but not as well as the editor whom he kicked out to please his well-placed friends.)

The conservative movement committed a supreme stupidity when it began expelling its greatest talent. In Sobran’s case, it threw a remarkable stylist overboard. He could construct elaborate theological and constitutional arguments with an economy of words.

It is not that Joe wrote on topics that no one else at NR was addressing. Many of his themes—such as liberal hypocrisy, Catholic orthodoxy, modern culture’s hedonism, and capitalism’s merits — were subjects that often surfaced in conservative publications thirty years ago. Joe was certainly not the only writer who engaged them. What should attract readers is his epigrammatic writing style and the offhanded way that he states deep insights. We are still combating many of the same things Joe went after thirty years ago, although the cast of characters is not entirely the same.

For me the most interesting statements in the collection are the ones where Joe examines the rise of PC. An awareness of this problem was not always apparent from his observations, and as late as 1977, when he wrote about the televised version of Alex Haley’s Roots, he gave the ABC producers and the author the benefit of the doubt despite the series’ inaccuracies and exaggerations:

The value of Roots is that it imaginatively provides American blacks with a legitimizing lineage, a therapeutic myth and beneficent stereotype acceptable to both races, fostering black self-assurance while actually minimizing white guilt.

Presumably only slave traders and slave owners were really “monstrous,” but modern whites were being let off the hook, or so it seemed to Joe in 1977. But he also observes in the same piece that certain New York Times critics were attributing a uniquely evil form of bigotry to all whites:

To suggest that white men are unique in their residue of tribalism is to get everything backward. We are really distinguished by the extent to which we cherish the human capacity for transcendence.

His indulgent attitude changed by the time he wrote about a racial incident that occurred in Howard Beach, a white enclave in Queens, New York on December 20, 1986. Some drunken white teens assaulted three black youths who had entered the area, and one of the threatened blacks ran into traffic and was killed. The New York Times and the rest of the liberal media went ballistic and spoke of a wave of white violence against blacks that was sweeping the country. Joe noticed that those who viewed the Howard Beach event as an relatively isolated incident were being treated in the media as “bigots.”

In this commentary Joe provides some of his later, best known observations:

Race may be noticed, but only for progressive purposes. You can even make invidious racial generalizations, as long as they’re about whites.

Moreover, although most people make sense of the world by operating through stereotypes, only sociologists and other authorized progressives are now allowed to speak about

…distinctive forms of group behavior….A ‘bigot’ can be defined as a guy who gets caught practicing sociology without a license…the ideology of the taboo-monger posits bigotry everywhere…just beneath the surface…in all the lacunae of idiomatic speech, more or less the way the old physics posited the ether filling all the unexplored spaces in the universe. They think it must be there, so for them it’s always plausible to impute it. “Civil rights” is now based on the presumption of guilt—against whites. If you’re not in lockstep with Progressive Attitudes, you’re a bigot until proven otherwise.

Although modern readers may take these conclusions for granted, at the time they were still terra incognita in Joe’s mind. He was simply becoming impatient with the media’s prevalent anti-white, anti-Christian sentiment, and he had begun to complain about the outrageous double standard being applied to different groups. This complaint first comes to the fore in the matter of race relations, but soon Joe would wander off the reservation by bringing up the Jewish liberal and Zionist predominance in the media.

The rest, to make use of a cliché, would be history.

Copyright © 2012, by Paul Gottfried and the Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation. A version of this column appeared in at TakiMag.com.

Paul Gottfried, Ph.D., is the Raffensperger professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

See a complete bio and other articlesTo sponsor the FGF E-Package:

please send a tax-deductible donation to the

Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation

P.O. Box 1383

Vienna,VA 22183

or sponsor online.

© 2012 Fitzgerald Griffin Foundation